Music of India: Know All About Indian Music

The ever-growing riches of Indian music is as diverse as the country's cultures, languages, and people. There are many different musical genres, such as classical, semi-classical, folk, and modern music, all of which are diverse in their procedures, renditions, and appeal, yet all of which are unified, like pearls strung together on a thread.

Exploring the various genres and traditions of Indian music and learning about them from the ground up would be a rewarding experience in and of itself. There are fascinating stories that every music fan either already knows or would like to hear.

What makes the music of India so vivid and vibrant? Let’s find out.

History of Indian Music

Music, dance, and performance has deeply integrated the culture of India through its religion, literature, and daily life in ancient India, with rich traditions across various regions and languages. Here are some of the evidences -

Paleolithic and Neolithic

The 30,000-year-old cave paintings at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh show people dancing and playing instruments like gongs, lyres, and dafs.

Stone musical instruments from around 4000 BCE were found in Odisha, and ancient cave carvings in Bhubaneswar show people singing, dancing, and playing music.

A 2500 BCE Dancing Girl statue and pottery paintings of people playing drums were found from the Indus Valley civilization site.

Vedic Origins of Performing Arts

The Vedas (1500–800 BCE) reference rituals that include music, dance, and theatrical performance. Texts like the Shatapatha Brahmana include dialogue in play form, and Samaveda explains early concepts of tala (rhythm) and melodic singing of hymns.

Musical Elements in Epics and Smriti Texts

Ramayana (500–100 BCE) describes dance and music performed by divine beings (Apsaras, Gandharvas). A variety of musical instruments: string (vina, bīn), wind (venu, shankha), and percussion. Use of ragas, vocal techniques, rhythmic patterns (laya), and poetry recitation in specific styles like marga.

Ancient Tamil Music (Pann System)

Tholkappiyam (500 BCE) and Sangam literature mention Panns, early melodic modes linked to landscapes and emotions. Panns evolved from pentatonic to heptatonic (Ezhisai), influencing Carnatic music.

Contributions from Various Regions and Saints

Jayadeva influenced Odra-Magadhi music and shaped Odissi Sangita. Śārṅgadeva's Sangita Ratnakara is a foundational music text for both Hindustani and Carnatic traditions. Madhava Kandali (14th century Assam) documented a wide range of musical instruments in his Ramayana version.

Documentation and Further Evolution

India's system of musical notation is considered one of the oldest and most detailed in the world. The concepts of Nritya, Vadya, and Geeta, out of which ‘Sangeeta’ evolves as a genre, find mentions in Yaksha’s ‘Nirukta’ studies - one of the six Vedangas. Besides, ancient Hindu texts such as Samaveda and Rigveda are composed of rhythmic and melodious verses.

However, the most ancient texts that formally laid out the grammar for classical music of India include Natya Shastra written by Bharatmuni and Sangita-Ratnakara by Sarangadeva.

Gandharva and Gana

Bharata classifies music into two types - Gandharva and Gana. Gandharva was defined as the Marga music that sang praises of Lord Shiva.

Legend has it that Lord Shiva used to teach the Marga music in his veena. In due course of time, Gandharva music, which was more formal in its composition and rendition, would be revered as the highest and the most chaste form of music.

Indian classical vocal and instrumental music in its purest form, and the way ragas evolved over time have their roots in Gandharva music.

In due course of time, Gandharva evolves into several other features for example sruti, jaati and gitika.

While Gandharva was meant to be staunchly composed for devotional purposes, Gana was meant for entertainment. Literally meaning song, Gana was meant to be a part of natya or drama.

Both Gandharva and Gana were different in their svarupa (structure) or the way they deployed swara, tala, and pada, phala (overall outcome of the composition and rendering), kaala (occasion and pretext), and dharma (a distinctive characteristic that defines both.)

The Classical Music of India

Broadly, there are two schools of Indian classical music - Carnatic music and Hindustani music. The Mughal courts contributed significantly to the development of Hindustani music in the northern half of the country.

Carnatic music arose in South India, and it is thought to have preserved the old approach to music.

However, there is much more to the history of Indian music than these two classifications. Here are a few snippets from the past, as well as a humble attempt to get to the root of Indian music traditions.

Learn more in detail about Indian classical music.

Raga, Tala and Pada

Much before the Mughals set foot in the Northern part of India, Indian classical music primarily had three fundamental elements - the ragas, talas, and pada.

The ragas - reiterating at least five or more Swaras (notes or micro notes) to form a baroque of melodious pieces or musical composition.

The talas use the time cycle to abide this musical piece into a rhythmic frame. It is the unison of Sur (tune) and tala that enhances the beauty of a musical composition.

The pada refers to the text that complements and adds substance to Swara and tala. It renders profoundness to the musical composition.

Gharanas of Indian Music

Gharanas are distinct musical lineages in Hindustani classical music, named after the regions where they originated, such as Gwalior, Agra, Lucknow, and Patiala. Emerging from the traditions of the Mughal courts, these styles later flourished in princely states. Each Gharana reflects a unique interpretation of vocal or instrumental forms like Khyal, Dhrupad, Thumri, Tabla, Sitar, and Sarod, adhering to strict stylistic principles. The tradition is rooted in the guru-shishya parampara, where knowledge was passed orally through dedicated training, often within families or to devoted disciples. This oral system preserved the purity of each style while allowing room for improvisation, enabling every Gharana to evolve with its own distinct identity.

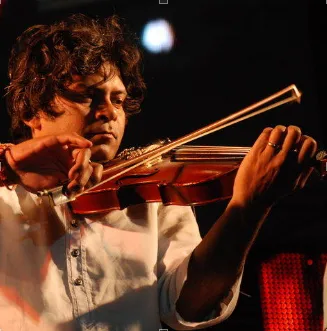

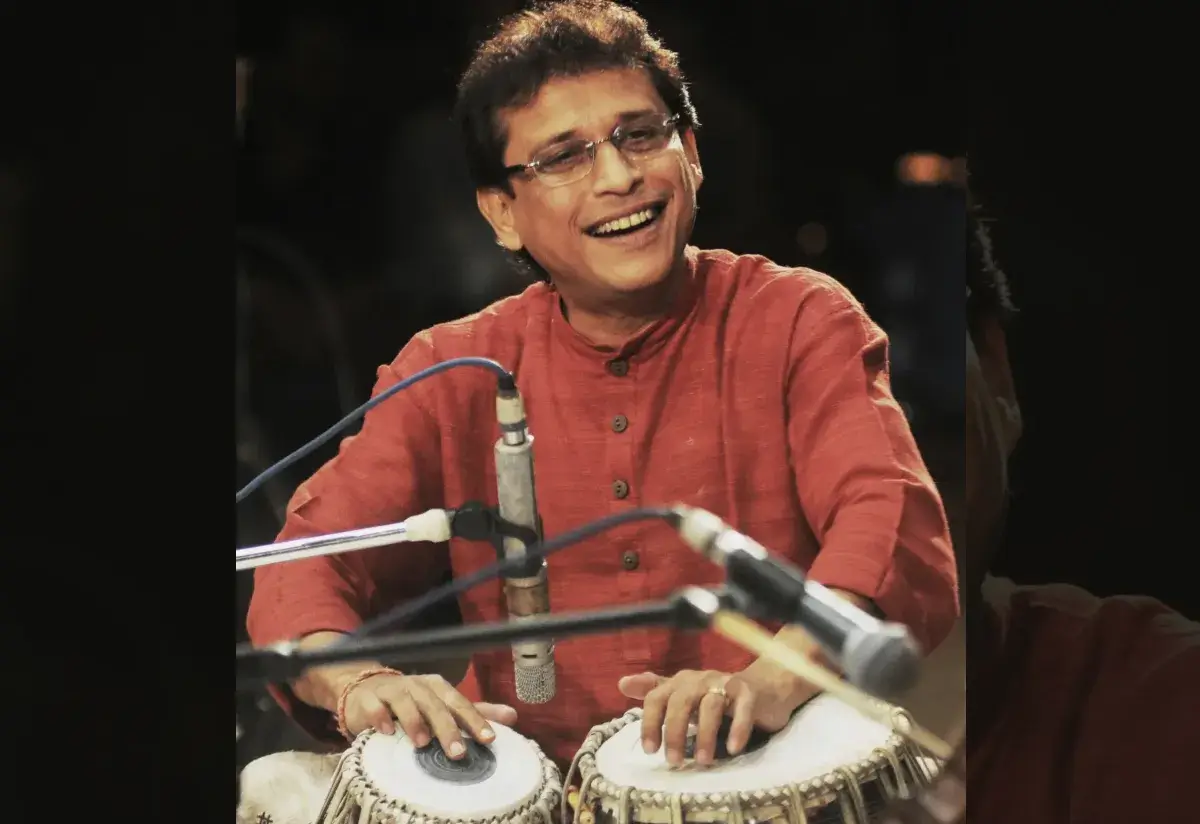

Indian Musical Instruments - Classification based on acoustic principles

Indian musical instruments are classified into four categories based on acoustic principles: Chordophones (string instruments) like Veena, Sitar, and Sarangi; Aerophones (hollow instruments) like Flutes and Harmonium; Idiophones (solid instruments) like cymbals and jal tarang; and Membranophones (covered instruments) like drums and tabla. While melody or raga evolved through vocals, chordophones, and aerophones, rhythm or tala developed with idiophones and membranophones.

We have covered Indian musical instruments in more detail in our other blog. Read about musical instruments of India.

Different Styles of Indian music

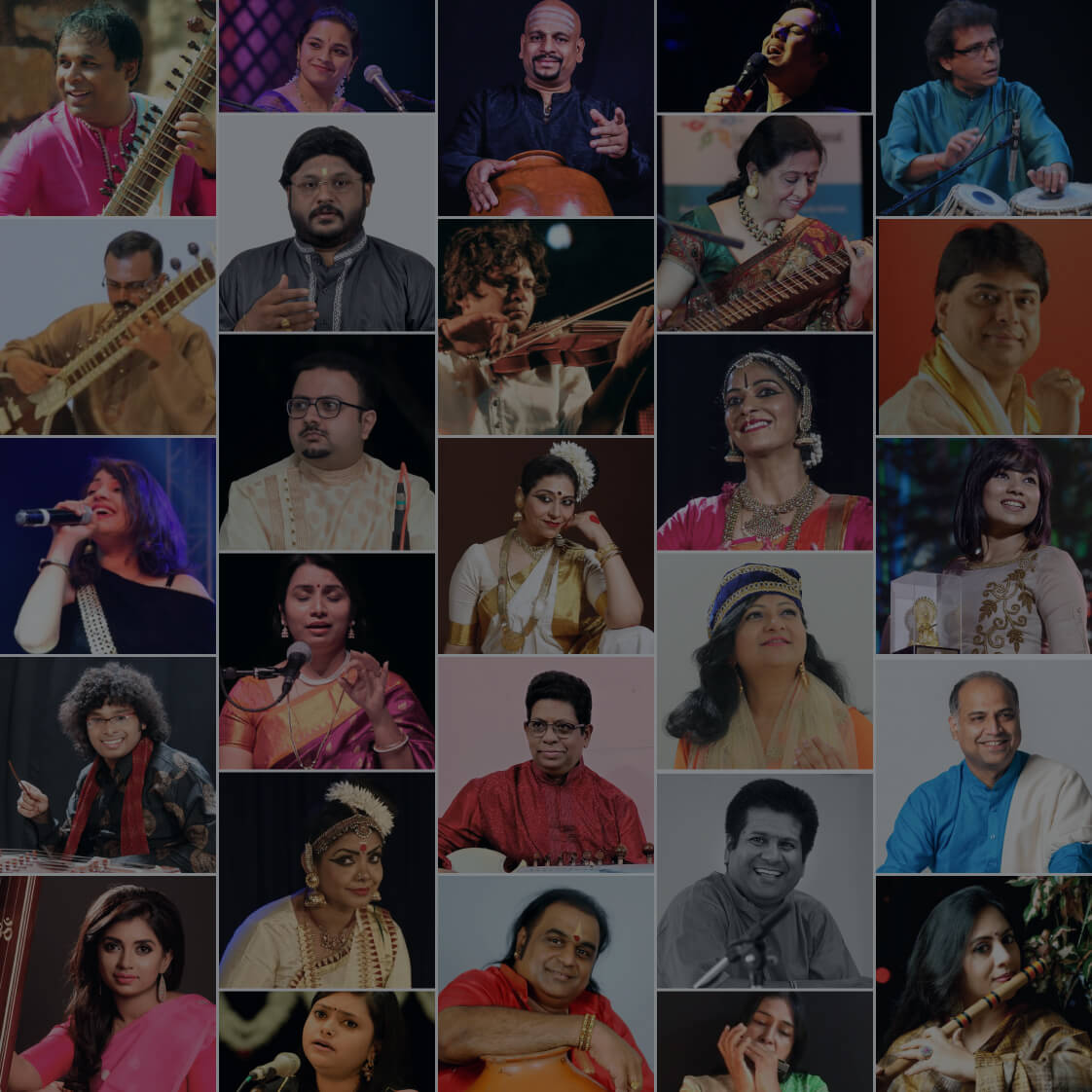

Mapping the types of Indian music is like counting the leaves of a tree rooted deep in civilization and endlessly reaching for the sky. From ancient traditions like Gandharva and Gana, countless musical styles have emerged. Today, Hindustani and Carnatic classical music thrive alongside a rich variety of regional, semi-classical, and folk genres. Reflecting the country’s cultural diversity, Indian music continues to evolve, with artists contributing to its growth and global recognition. Over time, it has also absorbed influences from Islamic and European traditions, enriching its already vast legacy.

Read in detail about semi classical music and several other Indian singing styles.

What makes Indian Music Unique?

Western classical music is harmonic. It involves several instruments being played together in sync with each other, for example - an orchestra or an opera. This involves a pre-composed structure that every performer has to follow. There is no scope for individual improvisation or contribution.

The scene with the classical music of India is different...

Indian music is melodic and supports solo performances. Its melodic nature supports continual enhancement and improvisation. It allows every performer or music composer the freedom to experiment with sur, lay, and taan and thus add their valuable inputs to the raga.

Concluding - Music of India

We have come a long way tracing the pug marks right from when music sprouted in India's soils. And it is only a lifetime of bliss to trace its evolution further as it foliages into the magnanimity as it is at present.

Moving ahead, the dialogues with foreign cultures only helped Indian musical traditions to grow richer and more opulent. In the subsequent chapters on ‘Different Musical Traditions in India,’ we will delve deeper into each facet of Indian music and map their growth trajectory further.

If you really like this article and share the same passion for music as we do, explore Indian music online classes.